Brasenose College from the High Street (late 19th century frontage)

LET ME introduce you to an Oxford College – Brasenose College – my old College in fact. It boasts alumni such as Sir Arthur Evans (he of Knossos fame – see my June blogs), Sir William Golding (Lord of the Flies), John Buchan (Thirty-Nine Steps), William Webb Ellis (for rugby fans – he invented the game), Colin Cowdrey (for cricket fans), Michael Palin (for Monty Python fans), oh, and David Cameron (for …..er …., well, he was there).

The Old Quad (16th century) – sun dial (1719) on left wall often recognized in Morse episodes (the dome top right is not part of BNC, it’s the Radcliffe Camera outside in Radcliffe Square)

Brasenose began life as Brasenose Hall around 1219, but it was founded as Brasenose College (BNC) in 1509 by Sir Richard Sutton, a barrister (who acquired the property for the site), and William Smyth, Bishop of Lincoln (who provided for the expenses of the building) and it received its Royal Charter in 1512 with the full name of ‘The King’s Hall and College of Brasenose’.

BNC coats of arms – to left is Smyth’s, to right is Sutton’s and in the centre is the See of Lincoln’s (the diocese in which Oxford lay in when the College was founded)

BNC coats of arms – to left is Smyth’s, to right is Sutton’s and in the centre is the See of Lincoln’s (the diocese in which Oxford lay in when the College was founded)

William Smyth (1460-1514) Richard Sutton (? – 1524)

The Old Quad (pictured above) is the original 16th century building, but then of just two floors. A third floor with dormer windows was added in 1635. The oldest part of the College is the 15th century kitchen from when it was part of the earlier Brasenose Hall (see below) – it has since been update once or twice – in fact, very recently. Between 1657 and 1666 the Deer Park (very small area and supposedly named as a sly dig at the massive Magdalen Deer Park), the New Library and the New Chapel were added to the south of the Old Quad building. Nothing much happened to the place during the 18th century due to lack funds (well, it had funds but most of them seem to end up in the pockets of the Principal and Senior Fellows – much to the annoyance of the Junior Fellows who complained bitterly ….. until they became Senior Fellows). Then towards the end of the 19th century the High Tower and New Quad adjacent to the High Street began to take shape (see pics at beginning and end).

Extent of BNC from the 16th century to early 17th century (north to the right)

BNC in 1674

Part (about half) of the Deer Park in foreground (I said it was small) with the New Chapel in the background

Interestingly, sport was rarely played by any of the Oxford Colleges before the 19th century – young men of Oxford in the 18th century, particularly, were of the drinking sort rather than the sporting sort (or even academic sort – only a few bothered with actually obtaining a degree in those days!). Sport began, unsurprisingly, with rowing, then, wot ho!, cricket. BNC acquired a good reputation in these two activities in the early days. In fact, since the races began in 1815, BNC runs 3rd with 23 victories as the ‘Head of the River’ (Oriel is 2nd with 30, Christ Church is 1st with 33).

A Saturday afternnon in May, end of Eights Week, the rowing viewed from the balcony of BNC boat club (with Pimms) is always a good crack

The College’s, shall we say, unusual name refers to a 12th century ‘brazen’ (brass or bronze) door knocker in the shape of a nose. The door knocker is said to date back to the 13th century and, from around 1279, marked the entrance to Brasenose Hall (an academic hall – independently leased in 1381 – before BNC became a College in 1509). In 1333, it is believed that the door knocker was removed by a band of rebellious students who migrated to Stamford in Lincolnshire. This rebellion was, in due course, suppressed and the students were ordered to return to Oxford – but without the knocker. In 1880, a house in Stamford came up for sale – it had been known as ‘Brasenose’ since the 17th century due to its door knocker which was thought to be the very one taken by the migrating students in the 14th century. BNC purchased the house to recover the door knocker! Well, spare no expense!

BNC’s 13th century door knocker now displayed in Hall

DON’T READ THIS PARAGRAPH AT NIGHT (you have been warned): BNC also has its legends. One of the more ‘infamous’ is the alleged brief composition of the Hell Fire Club (HFC) wherein demon worship – and a good deal of drinking – supposedly (well, only with regard to the former) took place. So, nearing midnight on a December eve in (reportedly) 1828, on returning to College via a dimly-lit Brasenose Lane, a Fellow of BNC noticed a tall character dressed in a long black cloak pulling a person through a ground floor window which was not only protected by upright iron bars but also reinforced with stout wire-netting (to prevent students sneaking out at night). The window was that of a known and degenerate member of the HFC. Preposterous of course. However, on hastily rounding the corner of the Lane and entering the College, the Fellow encountered much shouting and then took sight of a rush of a group of terrified gentlemen appearing into the Quad from the staircase containing the very room with the window just described above. The legend concludes by suggesting that the owner of the room had been mid-way through a blasphemous speech when he fell dead with a broken blood vessel. It may be inferred that the tall man in the black cloak was the Devil Himself coming to collect the soul of his own (this tale is recorded in the 1872 journal Odds and Ends). Of course, no mention was ever made of the identity or the alcoholic state of the Fellow who ‘witnessed’ the tall man in the black cloak performing this devilish deed.

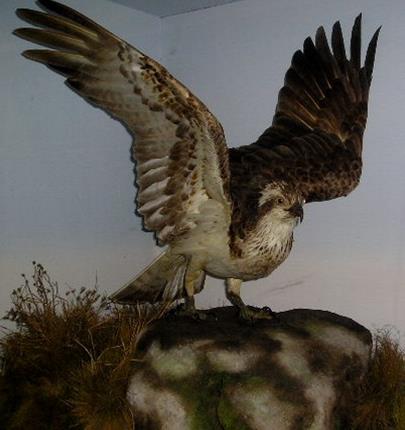

Soulless visitor to BNC

Not finished yet. The ‘legend’ then moves to archived fact. On the 3rd March 1834, Edward Leigh Trafford, a 21 year old undergraduate who had ground floor rooms with windows facing Brasenose Lane, and who, by tradition, was a president of the HFC, died of delirium tremens (the DTs – okay, ‘the horrors’!). Spooky, eh?

Brasenose Lane (BNC to the left) – avoid it at midnight, in case of drunken Fellows

During the 17th century BNC found itself in financial difficulties which worsened in the Civil War when Charles I made his headquarters in Oxford. He borrowed as sum of money from BNC for the conflict against the Parliamentarians. This, along with the 8% interest was never paid back – until November 2008…. by me in recognition of the 500 years of BNC (needless to say the sum is not comparable to today’s values and I did not include the interest as I had no statutory evidence that BNC was registered as a moneylender in the 17th century and therefore able to lawfully charge interest – that’s my story and I’m sticking to it!). I had read about the debt in Joe Mordaunt Crook’s 2008 book on Brasenose and the, then, Principal at BNC, Professor Roger Cashmore, wrote to me to say my contribution had been ‘immortalized in two speeches’ by him introducing the book on two occasions, but I’m still awaiting a note of appreciation from the present Royal Family …..

Talking of which, also to celebrate 500 years of BNC, the Queen visited BNC on 2nd December 2009 and was shown around the College by Roger Cashmore.

Roger Cashmore reminding Her Majesty of my generosity

The New Quad (behind the High Street – completed by 1911 – modern by BNC standards!)

Next week: Let’s go look at an Inn of Court

ASIDE

Did you know it was 70 years (and 5 days) since we sadly lost, as a result of a plane cash, the very talented Jimmy Stewart ……. sorry, Glenn Miller (I’m of the generation – I think most of us are now – that can never think of Glenn Miller without seeing James Stewart who memorably (obviously) played him in the 1954 film The Glenn Miller Story). Anyway, 15th December 1944, he (Miller not Stewart) was flying from an RAF base at Twinwood Farm, Clapham, Bedford, in the UK, to Paris to play to the troops, when his plane disappeared over the English Channel. It has been suggested that the most likely theory for the disaster is that the carburetor froze up in the cold weather. In fact, this was the cause of my father’s crash in his Wellington Bomber in 1940 resulting in him ending up in Stalag Luft III (of ‘The Great Escape’ fame – see end of that blog beginning of August).

Len Goodman of Strictly Come something is doing a radio prog on Miller which may be worth a listen. Click here,

Jimmy Stewart as Glenn Miller and Glen Miller as himself (which is which? – obvious when you see them!)

Artemus Smith’s Notebooks

I continue my research of the notebooks of Dr Artemus Smith, archaeologist of great courage, determination and fiction. Here is another extract:

I was in church with my old tutor from Oxford and we were just chatting whilst waiting for the start of the service, when, strap me, Satan himself suddenly appeared. Many of the congregation screamed to see God’s arch enemy and they all ran from the building. I was too astounded to consider a plan of action but simply exclaimed to my old friend (my tutor, not Satan), “Good Lord, what a scoundrel; damned impertinence, if you ask me!”

My tutor nonchalantly suggested that we stay where we were as there was no need for concern.

Now this clearly confused Satan and he walked up to my tutor and said, “Don’t you know who I am?”

My tutor replied, “Indeed I do.”

Satan asked, “Are you not afraid of me?”

“Not at all,” replied my tutor.

Satan was a little perturbed at this and queried, “Why not?”

My tutor calmly replied, “My dear fellow, I have been married to your sister for over 48 years.”