ANTIQUARIAN SOCIETIES are not old societies, they are societies for the study of the past (antiquity). Well, they are also old societies. One of the first to be set up was The Royal Society (of London for the Improvement of Knowledge) in 1660 (supported by the newly crowned Charles II) for the purpose of scientific learning. It still exists today, as does the Society of Antiquaries of London which was set up in 1707 at the Mitre Tavern in Fleet Street, with Humphrey Wanly as its first ‘chairman’. It received its Royal Charter in 1751. In fact, William Camden was a founding member of this Society in 1572, but it was suppressed by the Scottish born king, James I, in 1604, possibly because it encouraged English nationalism.

William Camden 1551-1623

The Society of Antiquaries was a ‘poor relation’ to the Royal Society which had greater resources of wealth and patronage. The former suffered various set backs including suggestions that its ‘board’ intended to subordinate itself to the Royal Society and, in 1792, its president, the Earl of Leicester, was accused of being a drunkard and a ‘brainless caput’ in a letter from Douce to Kerrich, 17th April, 1792 (Parker Library, Corpus Christi College, Cambridge) and by 1840 its members were deeply concerned about the Society’s purpose. However, it carried on in the shadow of other societies.

Heinrich Schliemann addressing the Society of Antiquities on his discoveries at Mycenae (The Illustrated London News, March 31, 1877) – I had the privilege of addressing the Society of Antiquaries on my work on Thomas Spratt RN in October 2013 after receiving my Fellowship of the Society

The Society of Dilettanti was set up in London in 1732 by Sir Francis Dashwood with the intent on focusing on classical antiquities, although, with its aristocratic and gentlemen Grand Tour members, it rather had an emphasis on dinning – Horace Walpole said of its members, ‘… the nominal qualification is having been in Italy, and the real one, being drunk’. It did produce some publications (three volumes of Antiquities of Athens and three volumes of Ionian Antiquities between 1762 and 1840) and kept alive an interest in classical antiquities.

Sir Francis Dashwood 1708-1781

The Royal Geographical Society was a learned society, founded in 1830 for the advancement of geographical science, under the patronage of King William IV and it was given a Royal Charter by Queen Victoria in 1859. Although not involved in archaeology as such, its later members were to take on a keen interest in the topic and equate it to landscapes studies. The Royal Geological Society had been formed in 1807.

Main Hall, Royal Geographical Society – impressive, eh!

In 1843, the Archaeological Association was formed but due to internal squabbling it soon split into two of the more important organizations: the British Archaeological Society and the Archaeological Institute, producing the Journal of British Archaeology and the Archaeological Journal, respectively.

The publisher, George Macmillian, was determined to keep up a following for the ancient Greek world and, in 1879, set up the Society for the Promotion of Hellenic Studies. Its purpose was to assist and guide English travellers in Greece and encourage exploration and excavation of ancient sites. Thereafter, in 1886, the British School [of archaeology] at Athens (BSA) was established, then, on the island of Crete, an annexe was set up at Knossos in 1926 – although the BSA had been involved with Knossos since the establishment of the Cretan Excavation Fund in 1899.

Library, British School at Athens (I’ve been there – it’s fantastic!)

Many county based societies for local history and archaeology appeared during the 19th century. But although these societies were limited in their appeal they did attract large memberships and, in some cases, from elite personnel. In fact, the Sussex Archaeological Society (1846) was criticized for snobbism for its open courting of the aristocracy (9.5% of its first year’s members were titled). Can’t image why!

Michelham Priory, owned by the Sussex Archaeological Society

Regardless of the varying internal politics (and, in some cases, external derision) of these societies, they gave credence to the new ideal of archaeology. Yet even now there are some who still frown upon the thought of 19th century ‘archaeologists’ when considering today’s methods which is a little unfair based on the fact that all new ideas have to start somewhere. It is not as if the ‘science’ relied entirely upon itself – Pitt Rivers, in 1884, acknowledged the need for assistance in other scientific fields such as geology, palaeontology and physical anthropology.

Lt-General Augustus Henry Lane-Fox Pitt Rivers 1827-1900 (go see his museum in Oxford – its great!)

The other importance of these societies is that, either by way of talks or publications in their journals, they brought to the fore the activities of some of these travellers and publicised their findings which otherwise would have little value. And their existence gave me something else to study!

.

Next week: Gladiator: Hollywood fact or fiction?

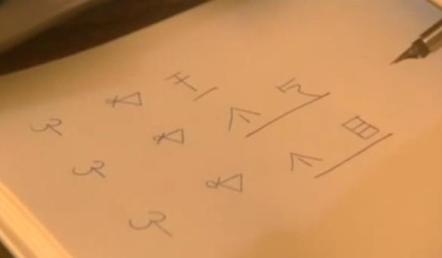

Artemus Smith’s Notebooks

I continue my research of the notebooks of Dr Artemus Smith, archaeologist of great courage, determination and fiction. Here is another extract:

My good friend Professor Schwartzburger said to me the other day, “I have just bought a new hearing aid. It cost me two thousand pounds, but it’s state of the art. It’s perfect.’

“Really,” I replied, “what kind is it?”

“Twenty past twelve.”