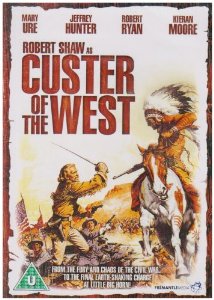

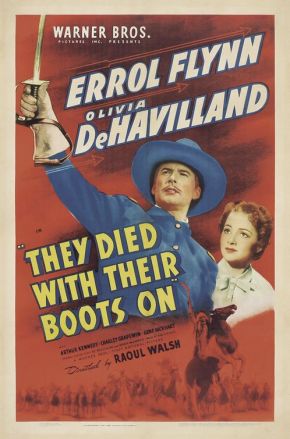

CUSTER OF THE WEST starred Robert Shaw in the lead role in 1967 and was a vague representation of the facts of the ‘Battle’ of the Little Big Horn and Custer’s last stand. There was also a rather less factual Errol Flynn version in 1941 called They Died with Their Boots on. What the 1967 version sadly lacked, which the 1941 version seemed very proud of, was the tune ‘Gary Owen’ which was taken up by Custer as the 7th Cavalry’s march – to hear it Click here (need sound of course).

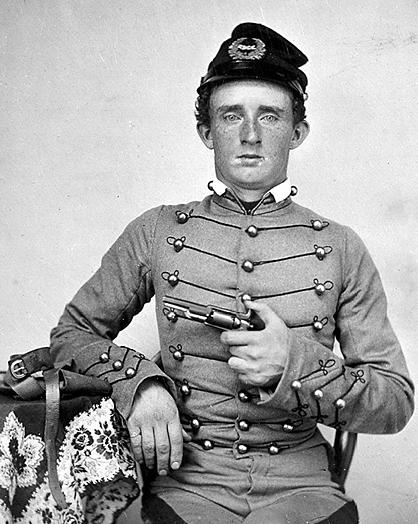

George Armstrong Custer was born in December 1839 in New Rumley, Ohio. He went to West Point in 1857 and graduated last in his class in 1861 just in time for the commencement of the American Civil War in April of that year. He performed courageously under the command of General George McClellan who saw to his promotion to acting captain but when McClellan was relieved of his command, Custer was reverted back to lieutenant. General Alfred Pleasonton took over from McClellan and under him came Custer’s introduction to the world of extravagant uniforms and political maneuvering, and the young lieutenant became his protégé and soon regained his rank of (full) captain. Custer distinguished himself by fearless and aggressive actions in some of the numerous cavalry engagements and he was rewarded (and so not by mistake as in the Errol Flynn film!) with promotion as the youngest brevet [1] brigadier of the volunteers at the age of 23.

Cadet George Custer at West Point, c 1859 – to be last in his class on graduation in 1861

Whilst on leave during the Civil war he married Elizabeth ‘Libbie’ Bacon in February 1864. Her father was Judge Daniel Bacon who, initially, had not approved of Custer as a match for his daughter as he (Custer) was the son of a blacksmith. Well, this all changed when Custer had become a hero of the Civil War ….. oh, and a brigadier general.

Brevet Brigadier General Custer, 1865

When the war ended, Custer was returned to his rank of captain but it was not long before he was commissioned a lieutenant colonel and assigned to the newly formed 7th Cavalry based at Fort Riley in Kansas where he joined the General Winifred Scott Hancock campaign against the Cheyenne ‘Indians’/Native Americans (see last post – I need to call them ‘Indians’ for context purposes). However after the Hancock campaign, Custer was court martialled for going absent without leave (AWOL) – he had become indifferent and frustrated with the campaign and abandoned his post to go and see his wife – and he was suspended from duty for one year. He returned to duty before the suspension had expired at the request of General Philip Sheridan who wanted Custer for the Indian campaign.

Libbie Custer (1842-1933)

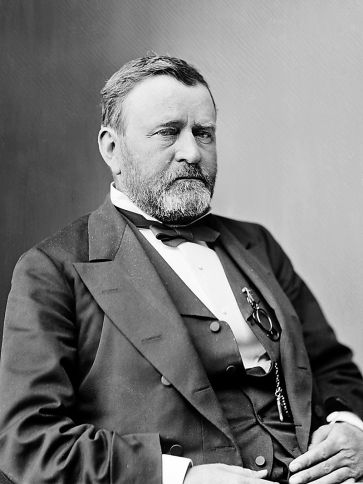

Now the Indian campaign took a bit of a turn when gold was found in the Black Hills of Dakota. These hills were owned by the Lakota Sioux Indians headed by Chief Sitting Bull as a result of the Treaty of Fort Laramie in 1868. The government needed to control them because of the gold and the fact that 15,000 miners had moved into the Hills setting up towns such as Custer and Deadwood (remember that place from Wild Bill Hickok post August 23, 2014). So, in the autumn of 1875, the government offered Sitting Bull $6 million for the land but the sum was turned down. President Ulysses Grant then made two fateful decisions: (1) he would not stop miners flooding into the Black Hills; and (2) all Lakota and Cheyenne Indians must report to the reservations by January 1876 or be treated as hostiles (thus reneging on the Fort Laramie Treaty). The Indian tribes refused to comply.

Sitting Bull portrait

This seemed to be a great opportunity for more glory for Custer. By now he had been gambling and making bad business decisions and was in severe financial difficulties and needed a ‘way out’. A campaign against the Lakota Indians was a good option. Unfortunately he was called to Washington to give evidence at the Congressional Committee trying to discredit President Grant’s Administration’s handling of contracts with the Indian Agencies on the frontier. Custer managed to try and implicate the President’s brother, Orvil, which was a mistake. The President was furious and decided to keep Custer on the sidelines of the Indian war and ignored all requests from Custer to see him to apologise. Eventually, General Alfred Terry, who needed Custer, eventually got him re-instated. So, in 1876, he headed to the Back hills in search of redemption and glory.

President Ulysses S. Grant (1822-85)

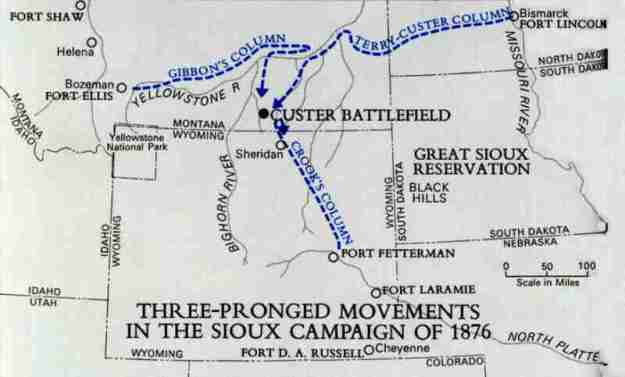

By January 1876 the Lakota Indians under Sitting Bull had not moved to the reservation and General Terry had orders to force him and his followers to do so or destroy them in the process. The plan was a three pronged assault on the Indian village of Sitting Bull’s alliance of Lakota Sioux and Cheyenne around Yellowstone River and four of its close tributaries, the Bighorn, Rosebud, Tongue and Powder (see map below). Terry (and Custer), with 1200 men, would approach from the east from Fort Lincoln; Colonel Gibbon, with 440 men, from the west from Montana; and General Crook, with 1100 men, from the south from Wyoming. Terry and Custer left via separate routes to clear up any Indian stragglers. Apparently Terry had said to Custer that if he (Custer) got there before him to leave him some action. Custer allegedly replied, simply, “No” (but I have no source for that…). Custer was a ‘dog off the leash’.

Plan of assault on the Indian camp at Little Big Horn

On the 25th June 1876, Custer, indeed, arrived about a day before Terry. Crook had arrived first and camped by the Rosebud River only to be attacked by a large force of alliance Indians under Crazy Horse and only just managed to avoid total defeat and retreated south. He reported this disaster to General Sheridan but made no effort to notify Terry. Custer wanted glory for himself alone and, despite the tiredness of his soldiers who had been on the move all day, he insisted on going into action immediately. As a result he split his force into three battalions, one under himself, another under Major Marcus Reno and the other under Captain Frederick Benteen. Neither of these officers liked Custer and the feeling was mutual, particularly as Reno was an alcoholic. Benteen was sent south and west, to cut off any attempted escape by the Indians; Reno was sent to charge the southern end of the encampment; and Custer rode north, hidden to the east of the encampment by bluffs, planning to circle around and attack from the north. This split was to prove fatal.

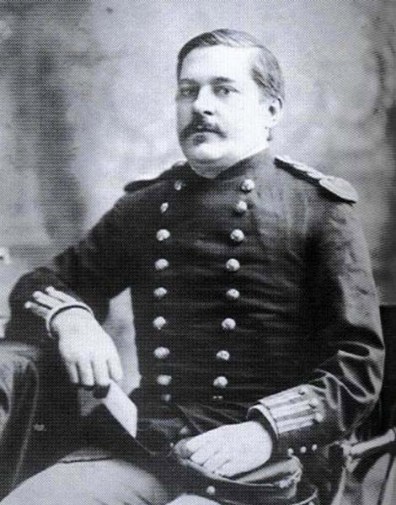

Major Reno (1834-89)

Custer had 208 officers and men under his command (including his two brothers, Tom and Boston, his nephew, Henry ‘Autie’ Reed, and his brother-in-law, Lt Calhoun), with an additional 142 under Reno, just over 100 under Benteen, 50 soldiers with Captain McDougall’s rearguard, and 84 soldiers under 1st Lieutenant Edward Gustave Mathey with the pack train. The Lakota/Cheyenne coalition may have fielded over 1800 warriors (although reports on this number vary).

Capt. Benteen, c1865

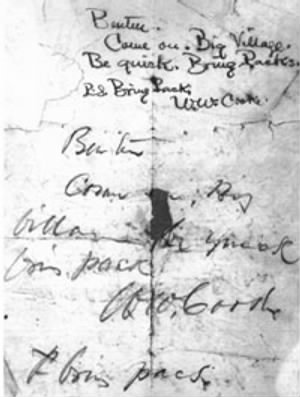

Reno was the first to encounter resistance when he was attacked some 500 yards from the village. He was forced to retreat back up into the hills having lost a quarter of his battalion. Here he met up with Benteen who asked where Custer was. By this time Benteen had received a note from Custer to come quick (see below) but he did nothing. In fact he and Reno sat and talked for about one hour and a half. A Capt. Thomas Weir, a friend of Custer, was so frustrated with Reno and Benteen’s inaction, particularly as they could all hear gunfire in the distance, that he rode off to investigate. Benteen was shamed into following him.

Capt. Thomas Weir (1838-76)

In the meantime Custer had arrived on the hill north of the Indian camp and saw it for the first time and realised how mistaken he had been about the number of hostiles involved. He sent the above mentioned note to Benteen, “Benteen, come on. Big village. Come quick. Bring packs.” He then waved hist hat and shouted, “Hurrah boys, we’ve got them. We’ll finish them up and then home to our stations” (bearing in mind there were no survivors I’m not sure of the source of this alleged quote – although one source suggests that a couple of Custer’s Indian scouts were sent away before the final battle). What followed was a complete massacre of Custer’s force. The precise details of Custer’s fight are largely conjectural since none of his men (the five companies under his immediate command) survived the battle. The accounts of surviving Indians are conflicting and unclear. Custer, himself, died with bullet wounds to the chest and head. With him on the hill were both his brothers, his nephew and his brother-in-law as mentioned above). This was indeed Custer’s last stand on ‘Last Stand Hill’ (as it is known today) as depicted in both Hollywood films, but not the last stand of his whole force.

Custer’s note to Benteen

Archaeology

There has been an archaeological survey of the battlefield which has produced some interesting results, including around 5,000 artifacts. The finds consist mainly of spent cartridges. It is known that the soldiers used the 1873 Springfield breach-loading ‘trapdoor’ carbine (a point the 1967 film fails to accept as, in the last stand, its soldiers use repeating Henrys/Winchesters), so finds of cartridges belonging to this gun indicate positions of Custer’s soldiers. Any other rifle cartridges indicate the positions of the Indians. It was discovered that the Indians were using 47 different types of guns from muzzle-loading ‘antiques’ to the modern repeating Henry rifle (similar to the famous Winchester). From such finds it is believed that at least 800 Indians were armed with a rifle of some description. Henry rifles had been given to the Indians by the government to shoot buffalo – there’s irony for you!

Above and below: the 1873 Springfield single-shot breach-loading ‘trapdoor’ carbine

It was these rifles that gave an idea as to why Custer failed in his encounter – other than being hopelessly outnumbered that is. Simply he allowed the Indians to get too close. The Springfield carbine is great at a long distance skirmish as it has an accurate range of around 600-700 yards, whereas the Henry repeater has an effective range of only 200 yards. However, once close-in the advantage reverses. The Henry can fire 13 rounds in 30 seconds compared with only 4 rounds from the single-shot Springfield. It doesn’t take rocket science to work out who the odds are against at short range affrays.

The 1860 Henry repeating rifle

The distribution of the cartridges indicated that something like a third (or more) of Custer’s men had been separated from Custer and killed before being able to join him on ‘Last Stand Hill’ (where Custer was found), about a third were killed on the hill and a third (perhaps less) killed trying to escape down the hill to Deep Ravine near the river Bighorn.

On top of Last Stand Hill near where Custer fell (see his marker) looking to Deep Ravine in the distance

In the distance from Last Stand Hill can be seen more markers of those who fell trying to escape to the river through Deep Ravine

.

Footnote

[1] A brevet was a warrant giving a commissioned officer a higher rank title as a reward for gallantry or meritorious conduct, but without receiving the authority, precedence, or pay of real rank.

POSTSCRIPT

One year after the battle, Custer’s remains and those of many of his officers were recovered and sent back east for reinternment in more formal burials. Custer was buried again with full military honours at West Point Cemetery on October 10, 1877 – a great honour for someone who finished last in his graduation class! The battle site was designated a National Cemetery in 1876.

Major Reno was dismissed from the army in 1880 due to alcoholism and died 9 years later. Benteen lasted a little longer but was suspended from duty due to being drunk and disorderly. He retired in 1888 but his inactivity at Bighorn continually hung over him.

Sitting Bull did not take a direct military role in the Battle of the Little Bighorn; instead he acted as a spiritual chief. He escaped to Canada but later found himself working for Buffalo Bill and his Wild West Show. He died in 1890 aged 58/59.

Sitting Bull (1831-90)

You can visit the site of the battle and it has a Visitors Centre (of course). But I did read a guide to the site which said, ‘Where ever you go, watch out for rattlesnakes!’

.

P.P.S. Finally, I always find these topics difficult because I love the Wild West and it’s ‘heroic’ characters. They are part of the ‘Great American Way’, However, the the more I read about Custer, the more I dislike him. Accepted, he was very courageous but that was part of his ego, arrogance and flamboyance – which got him the nickname ‘Lucky’ (he should never have lasted as long a she did with his crazy military antics). But that luck was to run out. I’m an avid supporter of the Native Americans and believe they were treated very badly by the US government and this leaves an imbalance with the ‘heroic romanticism’ of How the West Was Won. But that’s just my opinion.

Dr. Duds Dicta’s were a favorite to see in my “in” box. Rest in peace Dudley.

Much love

Rosanne and Peter Coumbis

Dr. Duds Dicta’s were a favorite to see in my “in” box. Rest in pease Dudley.

Much love

Rosanne and Peter Coumbis