IF YOU HAVE READ some of my previous posts on Homer and/or Troy you will know the Iliad. If you haven’t, you may still know the Iliad. Anyway, it’s Homer’s epic poem on the Trojan War (well, a short time towards the end, terminating with the death of the Trojan Prince, Hektor, at the hands of the Greek hero, Achilles).

Homer was an oral poet composing his epic tale around the 8th century BC about a war possibly taking place around the 13th century BC (see my post, ‘Troy: Hollywood fact of fiction?’ July 21, 2014). He followed it up with the Odyssey which tells of the lengthy return home from the war by Odysseus, another Greek hero.

Homer

As an oral poet, Homer did not write down his words of wisdom, but sang them as a form of entertainment. The Iliad was possibly first written down by order of the Athenian tyrant, Peisistratus, in the 6th century BC (but the ‘jury is still out’ on that). In the 4th century BC, Alexander the Great carried a copy of the Iliad with him wherever he travelled as he likened himself to the (almost) invincible warrior, Achilles (modest or what?).

Alexander the Modest (356-323 BC)

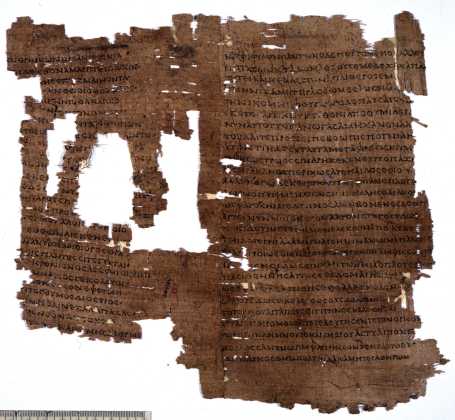

One of the earliest records of the work is in the Bodleian Library in Oxford. It is on a 2nd century AD Egyptian papyrus found by William Flinders Petrie in 1888 in a tomb of a female mummy in the cemetery of Hawara in Fayum, Egypt. It is in fragments and is the ‘catalogue of ships’ from Book 2 of the poem. It would have been a continuous scroll of about 30 ft in length.

The fragments of papyrus of the Iliad in the Bodleian Library

The fragments of papyrus of the Iliad in the Bodleian Library

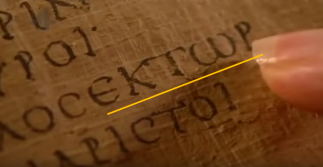

earliest record of Hektor and Achilles

Over the years some 1,550 Homeric fragments on papyrus have been found.

The Iliad on the the Oxyrhynchus Papyri III (Egypt, 2nd century AD)

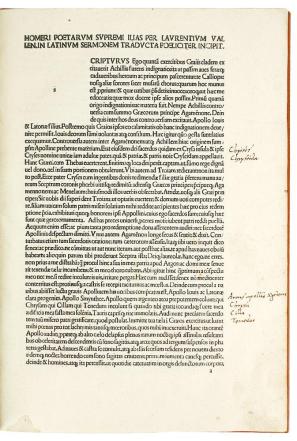

The Iliad was first printed in 1488 in Florence, and the first 10 books (of 24) were first translated into English in 1581 by Arthur Hall. He translated it, not from the original Greek, but from a French version by Hugues Salel published in 1555. However, the first celebrated translator of the whole of Homer’s Iliad into English was George Chapman (1559/60–1634).

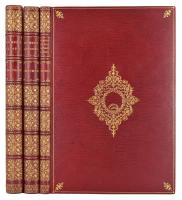

Now, you cannot buy a papyrus version (no surprises there) but the later printed copies are available occasionally – if you have enough money! As I write you can have a rebound 1611 edition of Chapman’s translation printed by Richard Field for Nathaniel Butter for £40,000 ($64,230); or a rebound 1497 second edition of Lorenzo Valla’s Latin prose translation at a bargain £18,500 ($29,700).

1611 edition 1497 edition

Alternatively, you can by a modern paperback version on Amazon for £6.99 ($10.78).

.

Artemus Smith’s Notebooks

I have discovered another volume of Artemus’ notebooks (followers will recall Dr Artemus Smith was an archaeologist of great courage, determination and fiction). Here is another extract:

I was given the opportunity of travelling the country with my talk on the Bronze Age of Mycenae. It was a standard talk but informative. My driver, Clarence, always accompanied me. One morning he said, “Do you know I have listened to your talk so many times I reckon I could give it just as well.”

“Right,” I said, thinking cheeky fellow, “tonight we’ll swap roles, you give the talk and I’ll drive.” He agreed.

I called my old friend, Rolo [Prof Rolande Circumspeque], who I knew would be in the audience that night and gave him a complex and unexplainable question to ask Clarence at the end. I was determined to the catch the blighter out.

That evening I drove Clarence to the lecture theatre and sat myself at the back.

Indeed he gave the talk without missing a beat, almost word-for-word as I had done it on so many occasions before. Then the questions. Rolo put up his hand and put the ‘complex and unexplainable question’ to him.

Clarence hardly stopped for thought. He looked at Rolo, smiled and said, “Ah, that is such an easy question that even my driver would know the answer, and to prove it I’m going to ask him to come down from the back and respond.”

One of my favourite tales