I have introduced you to some early British travellers to Crete (Spratt and Pashey in the 19th century, Pococke in the 18th century – see January posts) but now let’s go back even further to the 17th century and give you a taster of a couple of others.

William Lithgow (1582-1645)

Although the son of a wealthy burgess and educated at Lanark grammar school, Lithgow was not destined to be a scholar. Possibly to escape the ill-treatment by his brothers, he chose to travel and earn a living from his writings. He visited Crete in 1609 and recorded his travels in his Painefull Peregrinations (1632) but his tales and experiences on the island are mainly of woe. On his very first day he was robbed and nearly killed; he then rescued a French slave only to be chased and nearly slain by the slave’s ‘owners’; he was nearly bitten by three snakes having been led to believe that no such venomous reptiles could live on the island; and was to be the near-victim of an Englishman’s desire for the revenge of his brother killed at the hands of a Scotsman (Lithgow was a Scot). His action-filled narrative is somewhat exaggerated at times and it is never very clear which incidents, if any, are actually invented.

Lithgow dressed as a Turk whilst at ‘Troy’ (well, Old Illium)

He was disappointed with Greece having believed it to be a land of heroes now subdued by the Ottoman Turks and the same could apply to his view of Crete. He commented (keeping his early spelling):

“In all this countrey of Greece I could finde nothing to answer the famous relations, given by auncient Authors, of the excellency of the land, but the name onely; the barbarousnesse of Turkes and Time, having defaced all the Monuments of Antiquity: No shew of honour, no habitation of men in an honest fashion, nor possessours of the Countrey in a Principality. But rather prisoners shut up in prisons, or addicted slaves to cruell and tyrannicall Maisters.”

Title page to his 1632 book

If you go back to one of my June posts, you’ll see my reference to the labyrinth at Gortyns. Lithgow was there and he saw the entrance into ‘the labyrinth of Daedalus’ but did not venture into the cavern: “… I would gladly have better viewed, but because we had no candle-light we durst not enter, for there are many hollow places within it. So that if a man stumble or fall he can hardly be rescued.” He positioned it “on a face of a little hill, joining with Mount Ida, having many doors and pillars.” This must have been the site at Gortyns which is in the south east foothills of the Mount Ida range.

Lithgow and his attendant

In his Travelers to an Antique Land (1993), Robert Eisner said of Lithgow’s writing, “he does not, as they say in creative-writing curricula, bring scenes alive, but instead summarizes, ignores the particulars of the ruins he visits, generalizes, adds historical commentary, and then digresses.” In fact, his description of his fifty-eight days, travelling four hundred miles, is exceedingly brief and uninformative as far as any information regarding the island historically. His work was entertaining but not offering much to the learned traveller. But there we go, can’t all be perfect.

George Sandys (1578-1644)

Son of an Archbishop of York, Sandys was educated at Oxford as a gentleman of the University at the age of 11 in 1589, entering St Mary’s Hall but soon after transferring to Corpus Christi. He ‘grew into a gentleman famed for his learning in Classics and foreign languages.’ He was, as were several of his brothers and cousins, admitted to membership of Middle Temple (see one of my December posts) but he was not Called to the Bar as a barrister. Then, he would have had to have trained as a clerk for seven years but it appeared that he left after about a year to marry Elizabeth Norton. His uncle, Myles Sandys, was Treasurer of Middle Temple from 1588-1595. He travelled to Crete two years after Lithgow, in 1611.

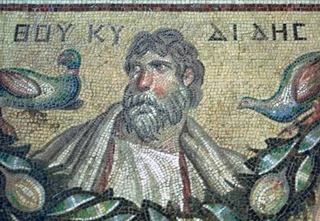

George Sandys

R.B. Davis (George Sandys, poet-adventurer: a study in Anglo-American culture in the seventeenth century, 1955) was of the opinion that Sandys did not actually visit Crete, “the ship did not put into any port on Crete, though Sandys does describe country dancing on the island as though he had seen it.” Davis possibly took this view because Sandys’ brief but stylistic report on the island made several references to ancient sources but no mention of visiting any sites or actually landing on the island. Sandys said he was “Much becalmed, and not seldom crossed by contrary winds … until we approached the South-east of Candy, called formerly Creta.”

Replica of 17th century Dutch East India Company ship – in search of Crete(?)

However, Sandys must have gone the island as, in his book, A Relation of a Journey Begun An. Dom 1610 … etc (1615), he described certain specific areas, such as Mount Ida and Gortyns and its labyrinth. He visited the labyrinth in 1611 but was a little vague as to whether it was actually at Knossos or Gortyns, although his reference to Ida would imply Gortyns as (as mentioned above) the latter is in the foothills of the former:

“For between where once stood Gortina and Gnossos at the foot of Ida, under the ground are many Meanders hewn out of rock turning this way & now that way … But by most this is thought to have been a quarry where they had the stone that built both Gnossos and Gortina being forced to leave such walls for the support of the roof, and by following of the veines to make it so intricate.”

Entrance to Gortyns Labyrinth around the 18th/19th century

Warren believed that Sandys was the first investigator of the cave when he remarked, “Sandys appears as the first British traveller actually to enter the Labyrinth.” Warren obviously didn’t count Lithgow’s visit in 1609 as he didn’t go into the cave (and rightly so – can’t get credit for doing things by halves).

Sandys’ references to other sites are rather limited and Warren’s comment of Sandys leaving a “full description of Crete in his book of 1615, packed with Classical scholarship and ancient history …” is somewhat of an exaggeration. He was certainly interested in Classical literature, having translated Ovid’s Metamorphoses and Book One of Virgil’s Aeneid, but of his travels, generally, he had little to say of antiquities, being more interested in mythology.

Mythology of Theseus and the Minotaur in the Cretan labyrinth

.

Artemus Smith’s Notebooks

I have now come to the end of my research of the notebooks of Dr Artemus Smith, archaeologist of great courage, determination and fiction. Here is the last extract:

I was obliged to write a reference for a member of my archaeological unit. It read as follows:

Casper Dempsey-Smythe can always be found

hard at work. He works independently, without

wasting the unit’s time talking to colleagues. He never

thinks twice about assisting a fellow employee, and always

finishes given assignments on time. Often he takes extended

measures to complete his work, sometimes skipping coffee

breaks. He is a dedicated individual who has absolutely no

vanity in spite of his high accomplishments and profound

knowledge in his field. I firmly recommend that he be

promoted to executive field officer, and a proposal will be

executed as soon as possible.

Addendum: The darn fool was standing over my shoulder whilst I wrote this reference, which I sent to you earlier today. Kindly re-read it, referring only to the odd numbered lines.

.jpg)

The Heel Stone

The Heel Stone